The transformative power of story is why we tell stories. Did you that that story is our primary means of how we learn, make meaning and sense of life? We learn through examples that are used in the form of a story. The exact details don’t actually matter as much as the arc of the storyline, and the lessons we take away from it. Storytelling is a uniquely human experience. In some ways it is the most natural form of human communication. All good stories have the capacity to be transformative. This is especially true of myths and fairy tales which show us fundamental truths by which man has lived for years.

The transformative power of story is why we tell stories. Did you that that story is our primary means of how we learn, make meaning and sense of life? We learn through examples that are used in the form of a story. The exact details don’t actually matter as much as the arc of the storyline, and the lessons we take away from it. Storytelling is a uniquely human experience. In some ways it is the most natural form of human communication. All good stories have the capacity to be transformative. This is especially true of myths and fairy tales which show us fundamental truths by which man has lived for years.

The real truth about story is that in some ways, that is all we are. By hearing each other’s stories we find relatedness and connection. It is by telling our story we see how we see it. From that place we have the possibility to recreate our own life story and achieve our most heartfelt desires. The key to getting what you desire is to change your story.

The transformative power of story starts with telling your story. This allows you to see the bigger picture, otherwise you can fall prey to seeing things in an ego-identified way… of ‘why me’ or ‘poor me.” When you learn how to change your story, to have a coherent narrative, you can change your life. This allows you to sense of and, therefore, be at peace with your life, because it connects the dots.

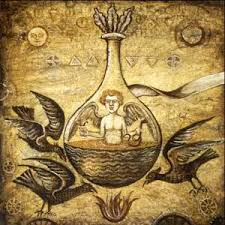

What about re-storying your life? That would mean you have to become the hero of your story… your true self. To do that I think it helps to become like a child again. Once a long time ago you had it, now it’s like paying hide to re-find it. Joseph Campbell identified in his ground breaking book Hero with a Thousand Faces the archetypal theme of the hero’s journey. The hero is the character that changes the most by the end of the tale. What I have found is that stories, just like life, follow the same simple formula: the protagonist which is synonymous with “the ego” wants something. There is conflict as to why the main character (the ego) cannot attain what is desired. Help is usually found when all seems lost, the conflict gets resolved, the ego part of the self attains some wisdom and becomes the hero as a result of the ordeal. This is where life and story can differ. It is through the ordeal that the main character (the hero) is somehow transformed. This is called the character arc when the ‘true self’ is reborn.

The royal road to the transformative power of story usually involves redemption. Redemption means a recovery of something pawned or mortgaged. The real work of our life is to regain a sense of wholeness, or to re-find the true self, while keeping the ego intact. Redemption comes about when the character demonstrates a generosity of spirit about life, an ability to find the gold in the ordeal, as opposed to staying stuck. As a result of the ordeal, he is made a hero and perhaps helps others to find the gold in their lives.

This is what gives our lives meaning and purpose… helps us transcend and rise above playing the part of the powerless victim. This re-storying of life is a shift in perspective or a revelation of how we stepped up to be a hero. This shift has the power to change the situation or circumstance of our life.

C. G. Jung, the famous and wise Swiss psychiatrist summarized it as follows:

It is an affirmation of things as they are: an unconditional “yes” to that which is, without subjective protests—acceptance of the conditions of existence as I see them and understand them, acceptance of my own nature, as I happen to be. (Jung, 1961/1989, p. 297).

The antidote and key to change starts with acceptance; this is the ingredient that creates cohesion and ironically gets us closer to what we want. Before you become the hero, you may meet up with the trickster. That is why most people stop short of achieving what they desire and sometimes what we are looking for comes hidden behind or in the form of the trials and tribulations. In other words, sometimes you get what you need which may not what you thought you wanted.

Telling our stories, like remembering and making sense of our dreams, can be very helpful. Why is that? For one thing, life itself can be viewed as a story, one we weave that is in effect how we view the world and our experiences. The brain is wired to think in terms of stories. When we write, the creative process helps us to tap into the reservoir of our memories and emotions, story doctored into a coherent narrative. A well-told story has the capacity to help us experience the human condition vicariously. As we tell our stories, we also inspire others who need to hear our stories, helping both writer and reader make sense and create meaning out of life.

In some ways, all stories are somewhat autobiographical, emerging from our personal psychology. In the book Why We Write, edited by Edith Maran, many well-known authors talk about an almost magical absorption they experience when they are involved in writing. Terry McMillan describes it, “like being in love. I am consumed by the characters I’m writing about. I become them. It’s refreshing, like running a few miles, the way you feel when you finish,” (141)

One of the primary reasons people give for wanting to write is a desire to express themselves. Writing about something is a very different experience than talking about it. James Pennebaker, in Opening Up: The Healing Power of Confiding in Others, shows that writing our thoughts and feelings and linking them to stressful or difficult experiences, as opposed to just venting or talking about them, can be a healing experience. Extending the benefits of journaling, writing creatively is a different form of expression pulls material from our personal experience, but also transforms it into a story conforming to the classic tenets of story structure.

Aristotle’s Poetics defines the power of drama as evoking the emotions of empathy and fear in the reader. It creates and resolves conflicts, offering hope and inspiring people. If we have certain fears, then other people probably do too and will want to read about how our fears were resolved. As the protagonist in the story experiences the character arc, or personal development from trials and tribulations, in the process of writing or reading about it, so do we.

Studies show that the main reasons authors write are: to express our feelings, to help others, to educate, to give pleasure, to create passion and because it is therapeutic. I’ve found that writing also opens amazing opportunities to research things that interest me and thus to write about things that are provocative, emotionally captivating to me that I want to learn more about.

In that sense, writing creatively is not unlike narrative therapy. It helps us to understand ourselves and others. People who read a lot tend to rank higher on the empathy scale than those who do not. We can say the same for those who write stories. We are all living life by self-selecting a narrative; for each of us it is a personal interpretation of “me.” Writing helps us to learn more about who we are. We select aspects of ourselves, what we are passionate or curious about and transform them into a story. This is what is meant by creating healing fictions. We become our own therapist. We story doctor our own story and look at what needs to be changed to make it coherent. The goal is to identify what we are passionate about and to find the story idea with which we have the strongest emotional connection. Then we go on the creative journey to find our unique voice and bring it forward.

Anyone who has always had a secret desire to write creatively must first come to terms with their “why” for writing. It is not necessarily to become rich and famous as a writer, but to write because we have calling. If you are writing simply to satisfy a yearning to tell a story of some sort, you only need to consider your own tastes. But if you are writing with the goal of publishing, you must consider your readers as well. Readers know what they like and don’t like but can’t always tell you why. The answer always resonates with how the mind is’ wired for story’ as Lisa Cron who wrote the book on that would say. Knowing your why will help you connect vividly and with discipline to your story.

Terry McMillan, quoted in Why We Write, edited by Meredith Maran (New York: Penguin Group, 2013.

What is the Imagination

What is the Imagination